Historical Fiction Sensitivity Checker

This tool helps you evaluate historical fiction based on key criteria discussed in the article. Answer the questions honestly to get a nuanced assessment.

What is the author's relationship to the historical period and cultures they're depicting?

How are marginalized groups portrayed? (Select all that apply)

Does the work acknowledge its fictionalized elements?

Did the author consult with historians or descendants?

How does the work handle systemic oppression?

Excellent Representation

This work likely centers marginalized perspectives and acknowledges historical complexity. Good example of ethical historical fiction.

Moderate Concerns

This work shows good intentions but has notable issues. Marginalized voices may be present but limited or framed through privileged perspective.

Highly Problematic

This work likely misrepresents history through harmful stereotypes or silencing marginalized voices. May reinforce colonial narratives.

Why this matters: Historical fiction shapes how we remember difficult pasts. When marginalized voices are erased or romanticized, it becomes another form of historical whitewashing.

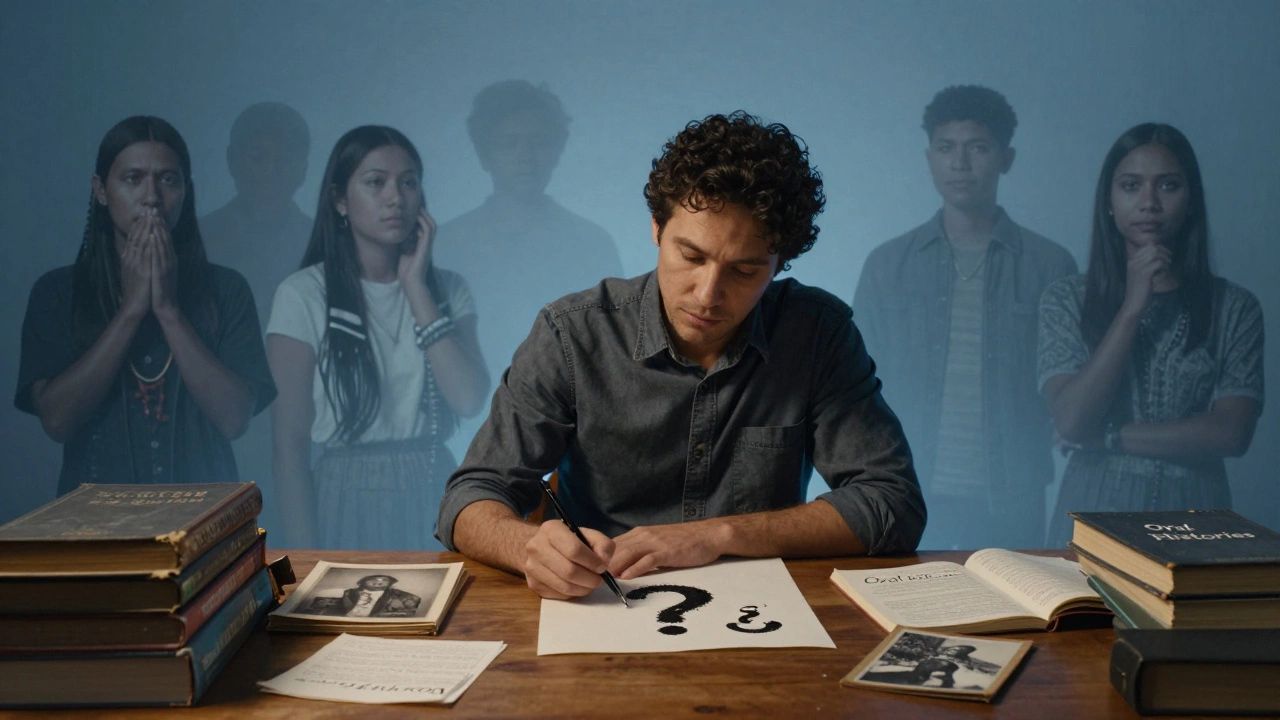

Historical fiction isn’t just about knights in armor or women in corsets. It’s about who gets to tell the story-and who gets left out. That’s why it’s so often controversial. When a novel reimagines the past, it doesn’t just entertain. It shapes how people remember wars, slavery, colonization, and revolutions. And not everyone agrees on what’s fair, true, or respectful.

It Rewrites Who Gets to Speak

Most historical fiction is written by people who didn’t live through the events they describe. That’s not a problem-unless those stories erase the voices of real people who did. Take the American Civil War. For decades, novels and films portrayed Confederate soldiers as noble gentlemen defending their way of life. Meanwhile, the brutal reality of slavery was minimized or ignored. Even today, some bestselling historical novels give white plantation owners complex inner lives while making enslaved people silent props in the background.When authors write from a position of privilege-white, Western, male-they often unintentionally center their own perspective. Indigenous Australians, Black slaves in the Caribbean, Vietnamese civilians during the war-these voices rarely get the same depth. When they do, it’s often through the lens of a white protagonist who "discovers" their suffering. That’s not storytelling. That’s appropriation.

Accuracy Isn’t Just About Dates and Uniforms

Readers expect historical fiction to feel real. But accuracy isn’t just getting the color of a soldier’s coat right. It’s about understanding power, language, and social norms. A novel set in 18th-century London might show a working-class woman speaking like a Jane Austen character. That’s not realism-it’s fantasy dressed as history.In 2021, a popular novel about the Tudor court got slammed for having a Black woman as a lady-in-waiting to Queen Elizabeth I. Critics said it was anachronistic. But historians pointed out: there were Black people in Tudor England. Records show at least 300 lived there. Some held positions at court. The controversy wasn’t about the character being Black-it was about the author treating her presence as a shocking twist instead of a fact.

Historical fiction often mistakes "what’s commonly believed" for "what actually happened." That’s dangerous. When a book claims a queen had a secret love affair with her servant, and millions read it, that becomes folklore. Soon, school textbooks start citing the novel as evidence. That’s how myths become history.

Commercial Pressure Distorts the Past

Publishers want books that sell. That means romance, drama, and clear heroes and villains. So historical fiction gets turned into soap operas with fancy costumes. Think of the endless stream of novels about queens falling in love with their bodyguards-or soldiers finding redemption through a kind peasant girl.These stories aren’t wrong. But they’re selective. They ignore the messy, uncomfortable truths. What about the women who were sold into marriage as children? The children forced into factories at age six? The families torn apart by land seizures? Those don’t make for pretty covers. So they get cut.

In 2023, a novel set during the Irish Famine became a bestseller because it focused on a wealthy landowner’s moral dilemma. The book didn’t mention the British government’s role in withholding aid. It didn’t show starving families eating grass. It showed tea parties and whispered regrets. The publisher called it "emotional." Critics called it historical whitewashing.

It Lets People Feel Good About Bad History

One of the most dangerous things historical fiction does is let modern readers feel like they’ve "understood" the past-without actually confronting it.A novel might show a kind slave owner who frees his slaves out of guilt. Readers walk away thinking: "See? Not all slave owners were monsters." But that’s not history. That’s wishful thinking. In reality, most slave owners defended slavery as natural, moral, and necessary. The idea that a few good ones made the system bearable is a myth that protects the guilty.

Same with colonialism. A novel might follow a British officer who "sees the error of his ways" and helps a local leader. The reader feels moved. But the real story? Colonial administrations systematically destroyed languages, religions, and economies. A single good officer didn’t change that. Yet fiction makes it seem like redemption was possible-when it rarely was.

Some Authors Try to Do Better

Not all historical fiction is problematic. Some writers do the hard work. They dig through archives, consult descendants, hire sensitivity readers, and admit when they don’t know something.Authors like Marlon James, whose novel Black Leopard, Red Wolf reimagines African mythology with deep respect for oral traditions, or Colson Whitehead, who turned the Underground Railroad into a literal underground train in his Pulitzer-winning novel-not to confuse facts, but to expose deeper truths.

Then there’s Hilary Mantel. Her Wolf Hall trilogy doesn’t try to make Thomas Cromwell a hero. It doesn’t sugarcoat his ruthlessness. It shows how power works in a world where loyalty was deadly and survival meant compromise. It’s not pretty. And that’s why it works.

These authors don’t pretend to have all the answers. They leave space for silence. They admit gaps in the record. They let the past stay complicated.

The Real Risk: History Becomes Entertainment

The biggest danger isn’t that historical fiction gets facts wrong. It’s that we stop caring about the difference between fact and fiction.When a Netflix series about the French Revolution shows Marie Antoinette as a misunderstood teen queen, people start believing she was innocent. When a video game lets you "play" as a pirate during the slave trade, you start thinking slavery was just another job.

History isn’t a costume party. It’s not a backdrop for romance or adventure. It’s the foundation of who we are today. Slavery shaped economies. Colonization shaped borders. Wars shaped laws. If we treat those events like plot twists in a novel, we forget their weight.

And that’s why the controversy matters. Because when we let fiction rewrite history without question, we let the powerful keep writing it for us.

What Should Readers Look For?

Not all historical fiction is harmful. But you should ask questions before you read:- Who wrote this? What’s their background?

- Does the book acknowledge gaps in the record?

- Are marginalized voices given depth-or just used as props?

- Does it challenge assumptions-or reinforce them?

- Is the author consulting historians or descendants?

Look for books that say: "This part is invented." "This is based on oral history." "We don’t know what happened here." That honesty is rare. And it’s powerful.

History Isn’t Set in Stone

Here’s the truth: history is always being rewritten. Every generation tells the past differently. The question isn’t whether historical fiction should exist. It’s whether it’s being used to understand-or to escape.Good historical fiction doesn’t comfort. It unsettles. It doesn’t give you heroes. It gives you questions. It doesn’t make the past pretty. It makes it real.

That’s why it’s controversial. And that’s why it matters.

Is historical fiction always inaccurate?

No. Many authors do extensive research and consult historians, descendants, and primary sources. The issue isn’t inaccuracy-it’s in what’s left out. A novel can be factually correct about dates and clothing but still distort meaning by ignoring systemic oppression, silencing marginalized voices, or romanticizing violence.

Can historical fiction be used to teach history?

It can be a starting point, but not a source. Historical fiction helps people connect emotionally to the past. But it should never replace textbooks, archives, or scholarly work. Always cross-check key facts. Many students mistakenly believe events from novels like The Book Thief or The Nightingale are fully accurate-when they’re heavily dramatized.

Why do people get upset when authors change real events?

Because real people suffered. When a novel turns a genocide into a love story, or a colonial invasion into a heroic adventure, it disrespects the survivors and their descendants. It’s not about being "politically correct." It’s about acknowledging that history isn’t a blank canvas-it’s a grave.

Are there rules for writing historical fiction?

There are no official rules, but ethical guidelines exist. Best practices include: acknowledging fictionalized elements, avoiding stereotypes, consulting experts from the culture being portrayed, and not centering white savior narratives. The most respected authors treat history as sacred-not as a playground.

Does historical fiction have value if it’s not 100% accurate?

Yes-if it’s honest about its limits. Fiction can reveal emotional truths that facts alone can’t. A novel might not get the exact date of a protest right, but it can show how fear, courage, or silence shaped people’s choices. The value isn’t in the accuracy of details-it’s in the depth of humanity it captures.